Introduction

Enamel matrix protein derivatives (EMDs) have been extensively evaluated in both pre-clinical (3) and clinical models. They are mainly composed of amelogenins, with smaller amounts of other non-amelogenin components, such as tuftelin, ameloblastin and enamel proteases (4). EMD is a biologically active compound that, once applied on a denuded root surface, starts a cascade of biological events, such as enhanced attraction and migration of mesenchymal cells, their attachment to the root surface (5), and differentiation into cementoblasts, PDL fibroblasts and osteoblasts. Enamel proteins enhance gene expression responsible for protein and mineralized tissue syntheses in PDL cells (6). This process may finally lead to reconstitution of the periodontal apparatus.

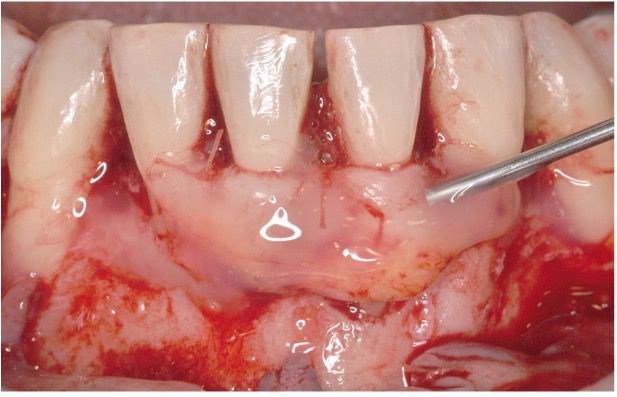

In this clinical case, we describe the successful regenerative therapy of a mandibular incisor with severe loss of periodontal support, utilizing Straumann® Emdogain® and a Connective Tissue Graft (CTG). This approach not only provided long-term stability for a tooth previously deemed to have a poor prognosis, but also helped meet the patient's expectations by allowing her to avoid complex surgical procedures and retain her tooth.

Initial situation

A 34-year-old female, healthy (ASA I) non-smoker with no medication, came to our practice complaining about mobility, gingival recession, bleeding, and suppuration from a mandibular incisor. The patient mentioned that the tooth began to move progressively several months ago, and her dentist applied a resin-bonded fixed splint between mandibular canines. Afterwards, she did not attend her follow-up appointments. The patient requested to keep her tooth.

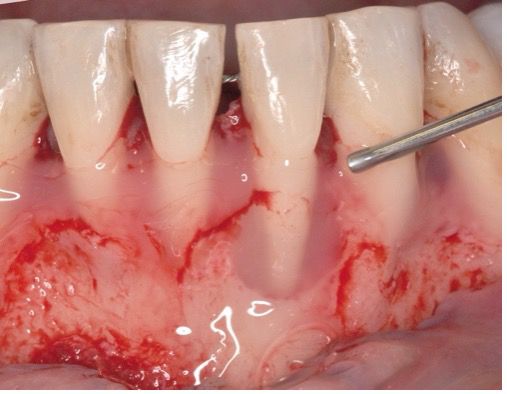

On the intraoral examination, a fixed splint was found from teeth #33 to #43; tooth #31 presented a thin gingival biotype, gingival recession on the buccal aspect with minimal attached and keratinized gingiva width, muscle and frenum pull, a probing depth greater than 6 mm, positive BOP (Bleeding on Probing), suppuration, redness and swelling, and dental plaque, suggesting a Stage III, grade B periodontitis (Fig. 1).

The radiographic examination revealed an extensive loss of periodontal support around tooth #31. (Fig. 2).